Music History 101: Lenny White

UP CLOSE

⭐️

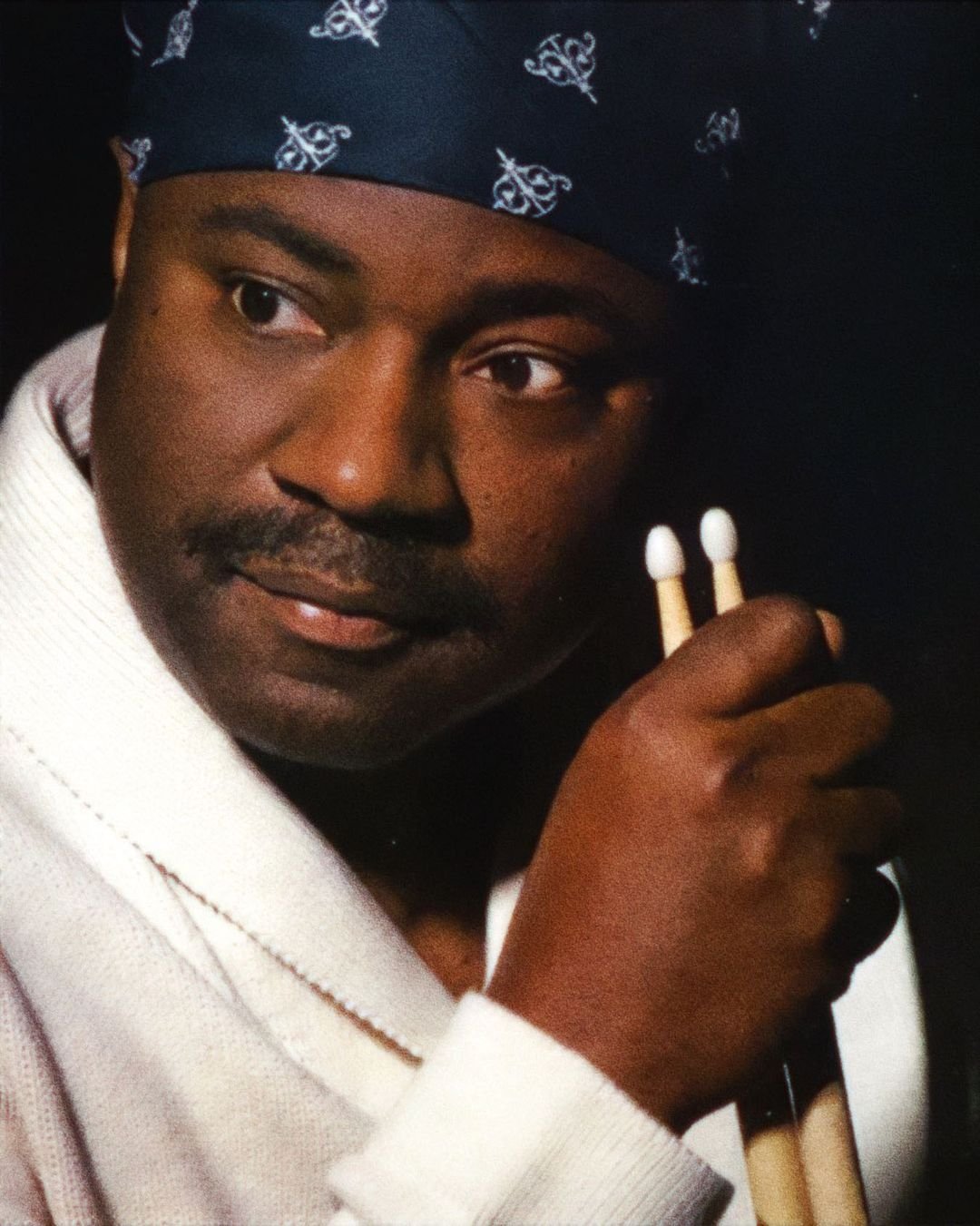

Lenny White

⭐️

UP CLOSE ⭐️ Lenny White ⭐️

Teaneck resident Lenny White has had a lot to do with moving the music forward in his illustrious career on the drums.

He came out of Jackie McLean’s band as teenaged prodigy, staying clean and avoiding the alto sax legend’s taste for heroin.

He was so good that word got through to Miles Davis who, in 1969, was putting a band together to play on his groundbreaking Bitches Brew.

It was there, in that studio, he met and hit it off with pianist Chick Corea. The two would ultimately change the face of modern music in the band Return To Forever.

Mike Greenblatt: How did you get to play with Miles?

Lenny White: I had gotten recommendations after playing with Jackie McLean. And everybody said if I played with Jackie McLean, I could play with Miles Davis because that’s what Jack DeJohnette and Tony Williams had done.

MG: You also played on two other pioneering jazz albums at the time: Passing Ships with Andrew Hill and Red Clay with Freddie Hubbard at Rudy Van Gelder’s historic studio in Hackensack. Miles, though, was notoriously mercurial and you were so young. Weren’t you totally intimidated?

LW: Everybody was intimidated with Miles Davis. But no. Miles was nice to me. He was a great teacher. How could you not learn something from being around Miles Davis?

“We went in, recorded in one take, and jammed. Then, afterwards, we listened, cut up the tapes, maybe moved a bridge, deleted a passage, or added a coda. Compositions were just not done like that at the time.”

MG: You once told me producer Teo Macero made Bitches Brew what it was by splicing it together in post-production.

LW: Not just Teo. He did it with Miles who had a unique perspective. We went in, recorded in one take, and jammed. Then, afterwards, we listened, cut up the tapes, maybe moved a bridge, deleted a passage, or added a coda. Compositions were just not done like that at the time. There was a strict 16-bar form you usually had to adhere to, then, and only then, go to the bridge, maybe repeat it, and change a key if you want. The way Miles did it, though, really changed everything.

MG: Your eyes must’ve lit up at playback because I don’t think that type of music had ever even been attempted before.

LW: There was no playback. Nobody heard the final mix. I was the only person. Miles called me. I went to his house. We sat and listened to the tapes. There was no one else there. In fact, none of the musicians heard the record until it was actually released except for me and Miles. I mean, sure, we listened to tapes but it still wasn’t final. I didn’t hear it either in its finished form until it was commercially released. What I remember was that there were things that happened at that session that we listened to in his apartment that day that never even made the final release. I swear I remember “Pharoah’s Dance” having a bridge and that just wasn’t there when the record came out.

MG: So Chick Corea asks you to join his new band, Return To Forever, and you initially turn him down.

LW: That’s correct.

MG: And, while at a San Francisco jam session, Santana’s Neal Schon asks you to join a new band he’s starting called Journey and you turn him down too.

LW: Correct.

MG: So what did you have going on at the time that you felt confident enough at such a young age to turn down both opportunities?

LW: I was already in a band called Azteca. Clive Davis had just signed us. It was the Escovedo brothers, Coke and Pete, doing a cross between Blood Sweat & Tears and Santana. We had four horns, three keyboards, four singers and four percussionists. Bassist Paul Jackson was in that band. It was also Sheila E’s first band. Trumpeter Tom Harrell was one of the horns. I had come from doing Miles’s record but this was a trend in popular music at the time to smash open genres to create something new. Clive wanted it. It was 1972 and I wanted to see it through. The whole time people were asking me to do this or that. But we finished the self-titled Azteca debut right around the time that Chick came to San Francisco with bassist Stanley Clarke. He at first wanted me to be part of a trio with him and Stanley. We actually worked at it for about a week before Chick then decided he wanted to do an electric band with lead guitarist Bill Connors [replaced by Al Di Meola an album later]. I explained to Chick that I just had to see this Azteca thing out to see how far it could go. Chick was cool with that and wound up getting session drummer Steve Gadd instead.

So there was a point where I found myself jamming with guitarist Neil Schon, bassist Ross Valory and drummer Gregg Rolie. Two drummers! Azteca had two drummers too. Neil was really psyched about this turning into a new band called Journey. I thought about it, sure, but Chick called back again, and this time I agreed to play with him and Stanley. [Azteca split up the following year after their second album, 1973’s Pyramid Of The Moon, failed to chart.)

Return To Forever 1972: (l-r) Lenny White, Chick Corea, Al Di Meola and Stanley Clarke

MG: The music you made with RTF changed my life. I was a staunch rock’n’roller but No Mystery and Romantic Warrior got me wanting to discover jazz. But then Chick, after your Grammy win, pulled the plug!

LW: I’ll never forget it. We were on the road in Kansas City when Chick told us he was going to break up Return To Forever. He was writing a piano concerto. I had a conversation with him backstage and told him, “Chick, go do your piano concerto. We won’t work while you do that. Just take off! But please don’t break the band up!” The band had momentum! But he wouldn’t hear of it. I think Chick had a love/hate relationship with Return To Forever. Decades after the break-up, not having played together for 32 years, RTF toured and recorded the Returns project. That’s when he told me the real reason he broke up the band. It had nothing to do with his writing a piano concerto. He admitted to me that he felt uncomfortable because the band had gotten too big. So big that he felt he was losing control.

MG: Tell me your seven drummers who are the building blocks of everything jazz.

LW: The Magnificent 7: Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes and Tony Williams. Those are the architects of Modern Jazz.

MG: I used to feel sorry for people who grew up without rock’n’roll until I realized that pre-rock youngsters had swing to go nuts over. But then bebop blew a big stick of dynamite under swing. You couldn’t dance to bebop but it was so much more hip.

LW: Bebop was the hip-hop of its day. Think about this for a second. When you hear a word like “hip,” that was invented in the bebop era. A lot of those terms, when hip-hop came to be, were borrowed from bebop. In fact, all music within jazz, rap and rock had an alternative duality. They all started out as underground: not being the norm of the day for American music. Now, those genres have become part of the culture-at-large. They are, in no way, counter-cultural anymore. Thus, unfortunately, there’s little innovation. Innovation has taken a back seat for commercial considerations.

MG: Artists today try to be so respectful to their antecedents in an effort to be valid that they’re afraid to be innovative.

LW: And so many folks find out about new artists from shows like American Idol, The Voice and America’s Got Talent.

MG: When you broke barriers and created sub-genres in the process, you were excoriated in the music press. I remember reading how jazz-rock fusion didn’t swing and would be the death knell for jazz.

LW: It’s come to be realized that Bitches Brew or bands like The Tony Williams Lifetime, Return To Forever, The Mahavishnu Orchestra and Weather Report were really jazz musicians refusing to play jazz the way it had been played. It wasn’t fusion like everybody called it. It was jazz-rock. The fusion part of it came later…

MG: …when it became more commercial. And critics reviled it, citing the arrangements as stiff and unyielding to what they considered true jazz. Do your students at NYU have any idea that you’re in the conversation as being the greatest living American drummer?

LW: [laughing] No, they don’t. And thank you for that. You have to understand that it’s OK, though, because it gives me somewhat of an advantage in leading them on at face value. After I talk with them and teach them something, they can go do their homework to discover who plays on what and go, “oh wow, this is the same dude with Miles, with Chick, teaching our class!” It gives me a challenge so I have to be up to par. I have to be able to make somebody realize something. Without talking down to them.

MG: They must look at you different after they make their discoveries. That’s so cool. But you’ve gone on. You certainly haven’t rested on past laurels. You produced Chaka Khan. You’re on the new album Air by The New York Bass Quartet. You’ve reunited with Chick and Stanley Clarke on a number of occasions. You’ve played with a huge assortment of artists all over the map.

LW: Isn’t that what a musician does? A musician plays music…whatever kind of music it is. I think what you have to do—and this goes for any young artist—is to continue to study so that when an opportunity arises, you’re able to rise to the occasion because you’re prepared.

MG: Good point. But not all musicians can do that as fluidly as you have.

LW: That’s true. But it wasn’t fluid for me either. I had a lot to learn. I listened to a lot of different kinds of music. Then I had to learn about them in order to be prepared and authentic about the music I was playing.

MG: I keep thinking about when you told me that the pandemic took away your purpose—performing—forcing you into delving deeper into composition.

LW: I had been working—touring and performing—for all these years, developing my musicianship, creating awareness of my art. Then it stopped. Cold. The pandemic took that away from all of us. We weren’t able to go out and perform. I thought about that a lot. I certainly had the time on my hands. So I figured, “let me go back to what I’ve been trying to do for quite a while, become a composer.” I took that opportunity to do just that. Hopefully now, it’s starting to be a realization. On April 4, I had my first classical composition performed by the NYU Orchestra. I’ve since been commissioned to write for a percussion ensemble. Now there’s a possibility that I might be able to take my new compositions to Copenhagen this November to see them debut with an orchestra there. In doing that, I know I have to study even more.